Park Days Decoded

Daniel Park

First introduced as the "Catalyst" in the third chapter of Disturbingly Normal, Daniel Park's philosophical take on life, psychedelic mindset, and charm, appealed to Lenzen like few character qualities have before. At the same time Lenzen felt a dynamic and engaging struggle within Daniel, one that would make the perfect vehicle for presenting the powers and pitfalls of the conscious mind. Kicking off with a narrative starting point five years following Daniel's first introduction as a character, with Daniel living on the streets as a derealized homeless man, Park Days was born!

The Artwork

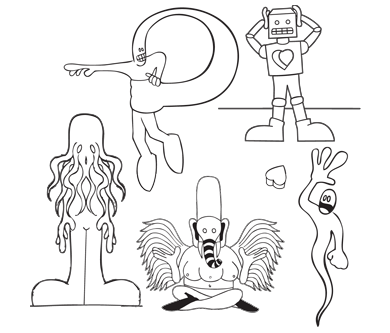

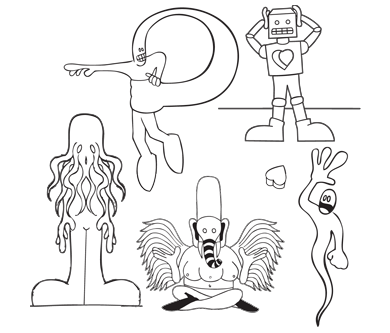

From Chapter 1 of Park Days: "Each page had a cartoonish character on it. Drawn in pencil or pen, the characters were metaphors for emotional states, unarticulated thoughts, and feelings..."

There are nine illustrations in Park Days. Imagined and drawn by J.D. Lenzen, each illustration symbolizes a milestone, provides insight into a struggle, or points out a challenge Daniel is about to face.

The Entertainer

The Entertainer

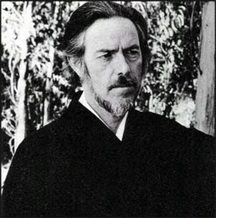

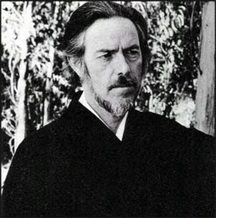

Alan Watts (1915 - 1973) once said, "I am not a Zen Buddhist. I am not advocating Zen Buddhism. I'm not trying to convert anyone to it. I have nothing to sell." Yet, despite his assurances, he's widely credited as having been one of the most impactful teachers of Eastern philosophy to Western students. Even to this day, Watts' books and audio lectures connect with people all around the world seeking insight into the nature of the mind and the universe. The Dutchman, Daniel's friend, sounding board, and watchful guide through Park Days, was inspired by Alan Watts and the element of irreducible rascality within him.

The Disappearance

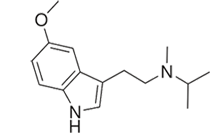

In the annals of psychedelic lore few stories are more perplexing than the (seemingly) sudden disappearance of Michael F. Carter. An occasional research collaborator with Alexander "Sasha" Shulgin (the pioneering chemist and drug developer), Carter lived and worked in Edgbaston, Birmingham (England), while Shulgin worked at his home laboratory in Lafayette, California (United States). Primarily communicating through letters, Carter and Shulgin's working relationship came to an abrupt end when, during the final stages of their research collaboration involving the methoxylated tryptamine 5-MeO-DIPT, Shulgin's letters began to be returned as undeliverable, or not returned at all. Despite extensive efforts, Shulgin was never able to reconnect with Carter. And to this day, Carter's whereabouts remain unknown. It is this enduring mystery that led Lenzen to include a plot point in Park Days that explores the possibilities of what might have happened to Michael F. Carter.

Carter's Last Words

Carter's Last Words

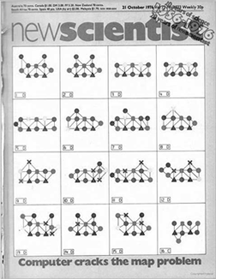

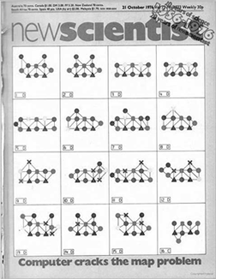

Research performed by Lenzen during the writing of Park Days revealed the last known address of Michael F. Carter. The address was first discovered on the title page of Shulgin and Carter's paper, "Centrally Active Phenethylamines", published in Psychopharmacology Communications in 1975. Carter's address at the time of the publication was 42 Constance Road Edgbaston, Birmingham B5 7RB. Knowledge of this address led to the discovery of a letter Carter sent to the New Scientist (a weekly international science magazine) one year later. The letter was published in the October 21, 1976 issue of the New Scientist, and Carter was responding to a pervious letter published earlier that month (October 7, 1976). To Lenzen's knowledge, the October 1976 letter to the New Scientist is the only publically available peek into the mind and personality of Michael F. Carter, and thus proved invaluable to the development of Carter's (Park Days) plot points. The text of the letter is provided below, accompanied by a link to the original New Scientist piece:

Psilocybin - A Letter by Michael F. Carter published in New Scientist, October 7, 1976:

First introduced as the "Catalyst" in the third chapter of Disturbingly Normal, Daniel Park's philosophical take on life, psychedelic mindset, and charm, appealed to Lenzen like few character qualities have before. At the same time Lenzen felt a dynamic and engaging struggle within Daniel, one that would make the perfect vehicle for presenting the powers and pitfalls of the conscious mind. Kicking off with a narrative starting point five years following Daniel's first introduction as a character, with Daniel living on the streets as a derealized homeless man, Park Days was born!

The Artwork

From Chapter 1 of Park Days: "Each page had a cartoonish character on it. Drawn in pencil or pen, the characters were metaphors for emotional states, unarticulated thoughts, and feelings..."

There are nine illustrations in Park Days. Imagined and drawn by J.D. Lenzen, each illustration symbolizes a milestone, provides insight into a struggle, or points out a challenge Daniel is about to face.

The Entertainer

The Entertainer

Alan Watts (1915 - 1973) once said, "I am not a Zen Buddhist. I am not advocating Zen Buddhism. I'm not trying to convert anyone to it. I have nothing to sell." Yet, despite his assurances, he's widely credited as having been one of the most impactful teachers of Eastern philosophy to Western students. Even to this day, Watts' books and audio lectures connect with people all around the world seeking insight into the nature of the mind and the universe. The Dutchman, Daniel's friend, sounding board, and watchful guide through Park Days, was inspired by Alan Watts and the element of irreducible rascality within him.

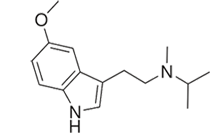

The Disappearance

In the annals of psychedelic lore few stories are more perplexing than the (seemingly) sudden disappearance of Michael F. Carter. An occasional research collaborator with Alexander "Sasha" Shulgin (the pioneering chemist and drug developer), Carter lived and worked in Edgbaston, Birmingham (England), while Shulgin worked at his home laboratory in Lafayette, California (United States). Primarily communicating through letters, Carter and Shulgin's working relationship came to an abrupt end when, during the final stages of their research collaboration involving the methoxylated tryptamine 5-MeO-DIPT, Shulgin's letters began to be returned as undeliverable, or not returned at all. Despite extensive efforts, Shulgin was never able to reconnect with Carter. And to this day, Carter's whereabouts remain unknown. It is this enduring mystery that led Lenzen to include a plot point in Park Days that explores the possibilities of what might have happened to Michael F. Carter.

Carter's Last Words

Carter's Last WordsResearch performed by Lenzen during the writing of Park Days revealed the last known address of Michael F. Carter. The address was first discovered on the title page of Shulgin and Carter's paper, "Centrally Active Phenethylamines", published in Psychopharmacology Communications in 1975. Carter's address at the time of the publication was 42 Constance Road Edgbaston, Birmingham B5 7RB. Knowledge of this address led to the discovery of a letter Carter sent to the New Scientist (a weekly international science magazine) one year later. The letter was published in the October 21, 1976 issue of the New Scientist, and Carter was responding to a pervious letter published earlier that month (October 7, 1976). To Lenzen's knowledge, the October 1976 letter to the New Scientist is the only publically available peek into the mind and personality of Michael F. Carter, and thus proved invaluable to the development of Carter's (Park Days) plot points. The text of the letter is provided below, accompanied by a link to the original New Scientist piece:

Psilocybin - A Letter by Michael F. Carter published in New Scientist, October 7, 1976:

|

"Sir,—I find it mildly surprising that an officer of the Metropolitan Police Forensic Science Laboratory can declare a bias in favor of a point of law that has clearly not yet been established — specifically the case of the Psilocybe mushrooms (Letter, 7 October, p. 60). The important point of the two court ruling in the matter, is not, as Mr. Jacobs suggests, that convictions can be obtained for possession of the mushrooms. If a magistrates' court can convict for possession and a Crown court dismiss an identical case, there must clearly be some doubt as to whether the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 covers the mushroom itself. |

In the case of other drugs of plant origin, the Act is quite clear. Cocaine is a restricted drug and the Act also includes the coca plant. The same is true of morphine and opium and THC/Cannabis. Psilocybin is a Class A drug, yet nowhere is there a mention of the mushroom.

There are additional questions that must also be asked if convictions can be obtained on this negative basis. How far is Mr. Jacobs prepared to extend the definition of "possession"? After all the mushroom can be found on many unsuspecting people's back lawns. There is a the matter of the drug mescaline and the peyote cactus |

in which it occurs. The 1971 Act does not include the cactus, and many a cactus lover's collection includes them and some people have used them for psychedelic purposes.

Two questions only are really important here. Should prosecutions be attempted on the basis of the existing law and should the Home Office be pressed into amending the existing law with all the difficulties attendant in this particular case. how is not the time to confuse the two."

Michael Carter

42 Constance Road Edgbaston Birmingham B5 7RB |